From www.astrology-and-science.com 16m 5g 66kb Home Fast-Find Index

Patron of research

A tribute to Charles Harvey 1940-2000

Arthur Mather and Geoffrey Dean

An expanded version of the original tribute in Astrological Journal 42(6), 45-46, Nov/Dec 2000.

Abstract -- Charles Harvey influenced the course of 20th century scientific research into astrology more than anyone else. His eminence within astrology, and his enthusiasm for scientific research, led to his becoming a key figure in the astrology-science debate. Without Charles there would be no Recent Advances, no Correlation, no London Research Conferences, no Kepler Days, no British research tradition to lead the world, and no websites like astrology-and-science.com. Like his mentor John Addey, he pinned his hopes on Neoplatonic ideas (true reality is intangible and manifests through number) and on a scientific revolution that would eventually validate astrology as a "systematic algebra of life and consciousness." Such an astrology, he believed, would heal mankind's ills by uniting spiritual and material values. Unfortunately research failed to support astrology to the extent that everyone had hoped, and in the years since his death the support has grown even weaker. The divide between astrology and science is still not bridged. Ironically Charles's efforts may have inspired a growing recognition, at least among researchers and innovators, that astrology is a spiritual endeavour not a material one. And with this, in contrast to his own belief, comes the need for a separation between perceived inner meaning and outward reality, between astrology and science, as the constructive way forward. Without Charles and the achievements he set in motion, the position today might be far less clear.

Charles Harvey influenced the course of 20th century scientific research into astrology more than anyone else. His achievements in mainstream astrology alone were extraordinary. Chronologically the main ones were: 1965 Astrological Association records officer, 1968 AA secretary, 1970 founder trustee of the Urania Trust, 1973 co-founder of the Cambridge Circle to develop harmonic astrology, 1973-1994 AA president, 1977-1986 Faculty vice-president, 1980 co-founder of ISCWA (Institute for the Study of Cycles in World Affairs), 1988 driving force behind the UT Astrology Study Centre and the acclaimed annual UT guide to astrological resources (effectively his own address book writ large), 1992 co-director of the Centre for Psychological Astrology, and 1994 AA patron, at which time it was estimated that Charles had devoted 19,000 hours of unpaid labour to the interests of astrology (Astrological Journal 36(5), 285-287, Sep/Oct 1994). In 1998 he named and launched the Sophia Project to guide a million-pound bequest for establishing astrology at a British university, characteristically setting up a meeting of astrologers and sympathetic academics to discuss options although he himself was too ill to attend. He passed away peacefully in his 60th year in February 2000. Over 300 people attended his memorial service in St James Piccadilly.

Respect for science

Charles's influence extended well beyond the traditions of astrology. It

was his enthusiasm and respect for scientific research that led to his

becoming a key link in the astrology-science debate. Without Charles

there would be no Recent Advances, no Correlation, no London Research

Conferences, no Kepler Days, no British research tradition to lead the

world, and no websites like astrology-and-science.com. Much was due to

his natural affinity for science (his two best school subjects were

chemistry and music), to his early close association with John Addey,

and to what Charles himself always stressed and admired -- doing instead

of talking. He knew that data and resources (of manpower, methodology,

scholarship) would be the key to genuine progress in research, and

worked unceasingly to acquire them. To us he represented the last link

with the original scientific foundations of the AA as envisaged by John

Addey and Brigadier Roy Firebrace.

In 1969 Arthur Mather was making regular research contributions to the original Correlation, pre-cursor of today's Correlation, when in the cafeteria of the Royal Festival Hall he had his first meeting with Charles to discuss research. Thanks to Charles he succeeded Fleming Lee as editor and in 1971 was appointed AA research co-ordinator. Charles's commitment to acquiring scientifically viable data blended perfectly with Arthur's own commitment to identifying scientifically viable tests. It was three years later, in 1974, that Geoffrey Dean first met Charles to discuss research. Charles was then living in Bromley and Geoffrey, temporarily returned to the UK from Western Australia, was staying in Chislehurst just a bus ride away. Without that slender coincidence of geography, and Charles's enthusiasm for research, the two of us (Mather and Dean) might never have met.

The first scientific survey

Our initial focus was a study by Geoffrey on aspects and lack of

aspects. In his inimitable way Charles encouraged us to widen the scope

and, once done, to widen it again, and then yet again, a daunting task

made feasible by Charles's contacts with astrologers worldwide, by the

AA Research Library that was housed in Charles's back room, by a large

boxful of scientific papers that Arthur had been collecting over the

years, and by Geoffrey's work that happened to involve the necessary

(and then rare) wordprocessing and photocopying facilities. After four

years of almost full-time work, Recent Advances in Natal Astrology was

published under the aegis of the Association, with Charles as one of the

major collaborators. It was a book of 608 pages including 17 pages of

index and 1010 references, both fairly rare in astrology books at that

time.

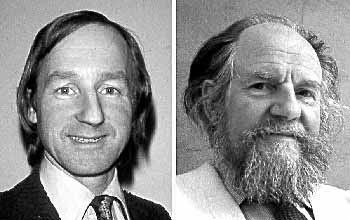

Charles Harvey (left) and his mentor John Addey in 1977 at the

completion of their long involvement with Recent Advances

As Charles himself puts it, the idea of Recent Advances was "to bring together all possible work that had been done in astrology, ... not necessarily critical, but attempting to see how astrology works, trying to understand better the principles behind astrology" (see Origins of Recent Advances under Historical on the home page). Its success in bringing together hitherto widely scattered facts and figures had been made welcome ("The most important book ever written on astrology" said Phenomena), but not its general lack of support for astrology, which led many astrologers into much rationalising after the event ("no room for empathy or universal wisdom" said Astrology Now).

Surge of research interest

Recent Advances led to a surge of interest in research, which in turn

led to the founding in 1979 of London research conferences, in 1981 of a

new Correlation and Urania Trust research grants (which in 1986 totalled

over #5000), and in 1990 of Kepler Days (small research conferences),

all of them a legacy of Charles's enthusiasm and seemingly endless

contacts. And with Charles's support we started on RA2, still on-going,

parts of which were subsequently published in various articles, book

chapters, and on the Web. We also ran three prize competitions for

evidence supporting astrology, of which the largest (the $US5000

superprize launched in 1983 for convincing evidence that astrology

cannot be explained by non-astrological factors) had numerous

co-sponsors including the AA and a panel of eight judges including Charles,

but no winners.

Unfortunately, when we reviewed for RA2 the outcomes of this new research activity, they failed to substantiate astrology to the extent that everyone had hoped. If anything the later picture got worse rather than better, which led to a perceptible distancing on the part of Charles, who was wedded to astrology and its interests above everything else. As he told us in person, but only much later in print, he felt that in Recent Advances and in our subsequent work we were too hasty in drawing conclusions from tests that he felt were inadequate. Charles's criticism was largely due to the Neoplatonic ideas he had inherited from John Addey soon after becoming active in the AA, and which guided his attitude towards astrology from then on.

Insights from harmonics

John Addey (1920-1982) was a remarkable combination of lucid and

eloquent writer, practical mystic, and unflagging experimentalist. He

was AA president 1961-73 and editor 1962-72 of its journal. His

Neoplatonic ideas had been set out in his 1971 Carter Memorial lecture

later published by the AA as a 24-page booklet Astrology Reborn. Addey

held that there is a Neoplatonic hierarchy from the highest organising

unity down to the lowest material plane, that astrology plays a central

role in this hierarchy, and that true reality is intangible and

manifests through number. He felt that the last was amply confirmed by

his empirical discovery of harmonics in astrology, which led to his

famous (and still unfulfilled) statement that astrology was about to be

reborn: "From being an outcast from the fraternity of sciences, it seems

destined to assume an almost central role in scientific thought" (p.1).

Charles Harvey chairs an expert panel at the second AA research

conference at the Institute of Psychiatry London in November 1981. It

was the AA's largest research conference and attracted 110 people. From

left are John Addey, Theodor Landscheidt (Germany), Charles Harvey,

Francoise and Michel Gauquelin (France), and Thomas Shanks (USA).

It was this claim, and Charles's enthusiasm, that resulted in Addey's harmonics receiving prominent treatment in Recent Advances, albeit not all of it positive. For example, contrary to what harmonics implied, the harmonic waves found in the Sun positions of 7302 UK doctors bore no relation to those of 6877 US doctors (p.150). Nevertheless, from now on, Addey's harmonic findings seemed to get progressively more positive while the conventional scientific findings seemed to get progressively more negative. This led Charles to believe that the negative findings were due to a failure to ask the right questions. But he still pinned his hopes on a more enlightened scientific approach eventually validating astrology.

These hopes are described in his essay "Ideal Astrology" in Tad Mann's anthology Future of Astrology (Unwin Hyman, London 1987, pp.71-80). Unlike most of the other essayists, Charles delivers what Mann's title promises. He predicts that full-time astrology courses will appear in universities "in the fairly near future", where huge banks of computer-analysed charts with portraits and case histories will lead to a better understanding of astrology. But before this can happen "many more astrologers will need to dedicate themselves ... to real astrological research." (He was obviously keenly aware of how astrologers generally showed little interest in serious research.) He stresses the need for empirical research: "we cannot evade the need for demonstrable, quantifiable evidence for astrological effects. ... Astrology works according to laws and principles, and much of the building of the larger future of astrology will depend upon the demonstration of these laws and principles in clear, unambiguous and often quantifiable terms."

Research philosophy

Charles's research philosophy (again inherited from John Addey) was very

clear -- if astrology is true then it can be shown to be true. But

despite his stressing that astrological effects "can be measured", he

became increasingly dismissive of conventional scientific attempts to

measure them. Thus in 1990, in the Astrological Journal 32(6), 399-402,

he criticises Recent Advances for "its constant willingness to draw

unwarranted conclusions from inadequate evidence" and most of the

controlled studies for being "from an astrologer's viewpoint ...

relatively simplistic." He comments "What is needed are really

thoughtful and imaginative experiments based on the way astrologers work

with astrology" and that "genuinely creative experiments depend upon

asking the right questions." He stresses that "this kind of research is

very difficult" and that "we are at the very, very beginnings of our

explorations." So it would be "foolish, and contrary to the principles

of good science, to abandon our first principles on the kind of negative

evidence produced to date." He ends by suggesting that the recognition

by science of Neoplatonic higher realms will result in a new science to

which "astrology must in due course become central ... In the meantime

for this to occur ... we do need better tests."

Charles Harvey (left), Arthur Mather, and Geoffrey Dean at the AA

Conference, University of York, 11 September 1983. Our disparate

geographies (respectively England, Scotland, Australia) made this the

only occasion on which we three met in person. Photo was taken on GD's

camera by the nearest bystander, who happened to be Michael Baigent.

This conclusion points to a difference in viewpoint between Charles and ourselves. Whereas we saw an absence of evidence as indicating "not proven", Charles saw it as indicating "not disproven." To him astrology was valid until proven otherwise, and even then any apparent disproof might be overturned by more sensitive investigations.

Reaction to negative evidence

During the 1990s his dismissal of negative evidence grew even stronger,

even though (thanks to computers and journals like Correlation) the

quality of research far exceeded anything reported in Recent Advances

twenty years earlier. Charles justifies this dismissal in an article

"Different Approaches to Astrological Research" in Correlation, 13(2),

55-59, 1994, where he identifies two distinct categories of research.

One is the scientific search for hard evidence, which is at "something

of an impasse." The other is the development of ideas, such as Ebertin's

midpoints, Rudhyar's cyclical approaches, Addey's harmonics, Lewis's

astro-cartography, Hand's composite charts, and the re-emergence (at

least in Britain) of Neoplatonic ideas.

Charles notes that "such major developments in astrology, with all their profound philosophical implications, are discounted or dismissed by most [conventional scientific] researchers as unproven, illusory, or as post hoc rationalisations to explain why any chart fits the facts." Yet an astrologer has a "sensitive awareness" of how astrology works and "knows that the same combination can express itself in a whole range of ways" that escape scientific scrutiny. Therefore "The more those of us researching astrology start thinking in the kind of symbolic and metaphorical language used by astrology, the more likely we are to come up with experiments which will produce convincing and interesting results."

This conclusion points again to the difference in our viewpoints. While it is true that scientific researchers tend to discount such developments, they do so only because they see a sensitive awareness of astrology's variability as an unawareness of nonfalsifiability. To us the argument would be more convincing if astrologers were not so ready to believe that astrology works while simultaneously failing tests that in many cases they themselves had helped to devise. Arguments about methodology do not explain why astrologers believe astrology works if astrology is so difficult to demonstrate under conditions where non-astrological factors are controlled. Or their seeming inability to meet Charles's urgent 1990 call for "really thoughtful and imaginative experiments based on the way astrologers work", or even to identify "the right questions."

Charles Harvey opens the combined AA-UT-NCGR 3-day research conference

at London's Palace Regent Hotel 20 November 1987. It was the AA's

second-largest research conference and attracted 90 people including 28

speakers from seven countries. In front of Charles is Neil Michelsen

(glasses). At far right are Michel Gauquelin and Suitbert Ertel.

Neoplatonic views

In his final book Principles of Astrology (Thorsons 1999), co-authored

with his wife Suzi, Charles re-emphasises his Neoplatonic view of

astrology. "Despite the contemptuous guffaws of scientific orthodoxy, it

[astrology] still continues to enthral the minds of some of our finest

contemporary thinkers." The reason is simple. Astrology sees the cosmos

as "a living, intelligent, purposeful entity in which part and whole

dance together in resonance to the music of the spheres; a hierarchy of

levels of order in which the higher levels order the lower and in which

the apparent random activity here on Earth below can be seen to be

orderly behaviour when viewed from the heavens above" (p.3). He notes

that Neoplatonic principles can be glimpsed by various divinatory

processes such as numerology and the tarot. "Where astrology is unique,

however, is in its identification of the way in which the movements of

the bodies of the physical solar system mirror, or plot out as on a huge

cosmic clock, the moment-to-moment processes of life. Armed with this

fundamental insight, astrologers over the centuries have been able to

develop a remarkable science and art for studying the creative potential

of any moment of space-time, be it past, present or future" (p.36).

Unlike his previous writings, there is no hint here of the need for better tests. The only empirical findings he cites in favour of the "remarkable science and art" are the positive findings of the 486Gauquelins. Their negative findings are not mentioned nor the existence of hundreds of other empirical studies. His chapter on resources lists sixty astrology books and journals but omits any reference to Recent Advances, to Correlation, or to anything scientific. Other than a brief aside there is not even a mention of John Addey's harmonic findings, possibly because Charles was aware that a study by one of us (GD) had shown they could reasonably be attributed to artifacts (Correlation, 16(2), 10-39, 1997).

Hopes of a scientific revolution

In the end Charles was receiving negligible support from the scientific

approach he had championed twenty years earlier during the compilation

of Recent Advances. Like John Addey before him, he was sure it would

lead to the scientific revolution promised by Astrology Reborn. To him

its failure could only be temporary. So he continued to pin his hopes on

an eventual scientific revolution, one echoed by physicist David Bohm's

idea of implicate order, where "a picture begins to emerge of astrology

as a systematic algebra of life and consciousness which is entirely

compatible with the new physics" (p.26). Essentially this was a version

of the ancient mystic idea of implicate spirit as the primary force in

the universe and explicate matter as its manifestation. For centuries

astrologers have made similar leaps of faith in pursuit of an

astrologically-friendly universe. But Charles's meticulous practice and

vast experience made him arguably more justified than most in making

such speculations.

Like John Addey, Charles believed that astrology would eventually revolutionise science and contemporary thought, and that it would heal mankind's ills by uniting spiritual and material values. But in the years since his death, empirical support for astrology has continued to dwindle. And as noted by American astrologer and historian James Holden, the idea of harmonics "has not found favor with most astrologers, and interest in it has waned" (A History of Horoscopic Astrology, AFA 1996, p.201). The divide between astrology and science is still not bridged.

Ironically Charles's efforts, unrewarded by the hoped-for results, may

have inspired a growing recognition, at least among researchers, that

astrology is a spiritual endeavour not a material one. And with this

recognition, in contrast to his own belief, comes the need for a

separation between the spiritual and the material, between perceived

inner meaning and outward reality, between astrology and science, as the

constructive way forward. The hoped-for revolution is not ruled out, but

it would still have to accommodate the results already obtained.

Nevertheless Charles's own work, and the achievements he set in motion,

have established a sound context for whatever may emerge in the future.

Working to clarify these fundamental issues would be a fitting tribute

to his life. Charles's contributions to astrology are commemorated by

the AA's annual Charles Harvey Award for outstanding service to

astrology. Recipients have been Liz Greene in 2001, Olivia Barclay in

2002, and Nick Campion in 2003.

Left. London researchers in 1983. From left seated are Charles Harvey, Danielle Claret, Jane de Rome, Mick O'Neill. Standing are David Stevens, Nick Kollerstrom, Rowan Bayne, Martin Budd, Simon Best, Patrick Curry, Michael Startup, Graham Douglas, Jonathan Cainer. Right. Charles's last book, dedicated "To all who would hear the music of the spheres"

Other tributes

The Charles Harvey memorial issue of the Astrological Journal 42(3),

May/June 2000 has 25 pages of tributes and recollections, many of them

extremely moving, from some of astrology's leading names around the

world. They illustrate Charles's outstanding contributions to astrology

in general, and how he touched the hearts and minds of everyone he met.

The astrology he loved was a topic afflicted by violent disagreements,

yet Nick Campion could note (in 1994) that "through the fourteen years I

have known him I have never once heard him utter a disparaging word

about anyone." Full obituaries appeared in the Times (reprinted in the

above memorial issue) and the Guardian. For a long obituary by Simon

Best, founding editor of Correlation, see Correlation 18(2), 3-8, 2000.

We thank Nick Campion for helpful comments.

From www.astrology-and-science.com 16m 5g 66kb Home Fast-Find Index